Mala Htun and Francesca R. Jensenius (2022). “Expressive Power of Anti-Violence Legislation: Changes in Social Norms on Violence Against Women in Mexico.” World Politics.

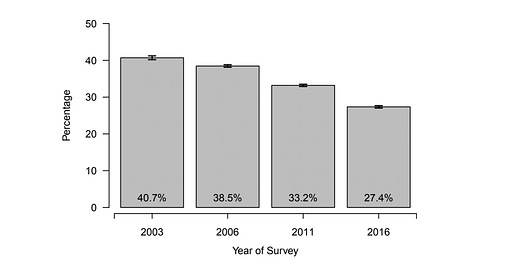

If laws criminalizing violence against women (VAW) are enforced poorly, as they are in many parts of the world, can they effectively deter violence from occurring in the first place? Using panel data from Mexico, Htun and Jensenius argue that they can. They take advantage of four rounds of data—2003, 2006, 2011, and 2016—from the Mexican National Survey on the Dynamics of Household Relations. For context, Mexico passed a landmark law in 2007 called “The General Law for Women’s Access to a Life Free From Violence” which, among other things, commits to reeducating and re-socializing men. Given the timeframe of the survey rounds, Htun and Jensenius see how trends in VAW change before and after the law is passed.

The results are below:

Actual reports of domestic violence go down:

Increased agreement on social norms regarding VAW:

Increased willingness to report violence amongst women. While the graph below highlights reports to family and friends, Htun and Jensenius find changes in the percentage of women who reported violence to authorities (6.5% in 2003, 5.1% in 2006, 7.9% in 2011):

The aforementioned results are stronger for women who know of the 2007 law. 84% of women in the 2011 survey said they knew of the VAW law of 2007, and this knowledge is a significant predictor of attitudes regarding VAW, propensity to report violence, and likelihood of experiencing violence—even after controlling for individual and geographic factors.

This paper was especially poignant given the latest resurgence in debates over criminalization of marital rape in India. A Delhi high court is set to make a ruling on Section 375 (Exception 2) of the Indian Penal Code, which prevents married women over the age of 15 from seeking legal recourse if they experience forced sexual intercourse from their husband. As this paper shows, setting a legal precedent may influence social norms. But elites may have to signal that social norms are ready to change in the first place (unclear if that’s happening in the Indian case, see here). For a read on how women’s rights change, check out Dawn Teele’s Forging the Franchise.

Abby Córdova and Helen Kras (2022). “State Action to Prevent Violence against Women: The Effect of Women’s Police Stations on Men’s Attitudes toward Gender-Based Violence.” The Journal of Politics, 84(1).

In a related paper to Htun and Jensenius’ paper above, this one finds that areas in Brazil with local women’s police stations lead to changes in attitudes and reports of VAW. Men are less likely to condone VAW and support bystander intervention. They also find lower rates on intimate partner violence in these areas. Both of these findings are stronger where women’s police stations have been operating for a while. To arrive at these conclusions, Córdova and Kras use an ordered logistic multilevel models with random effects while accounting for individual- and municipality-level differences. They also account for a series of alternative explanations. To name a few, they do not find the results stem from social desirability bias or the possibility that men are deterred from VAW due to policy enactment. They also do not find that the results are stronger in areas with a history of feminist movements.

In short, Córdova and Kras’ research suggests that women’s police stations at the local level change men’s attitudes and incidences of VAW. This is an important addition to the recent debate on the effectiveness of women’s police stations (see here and here).

Carreras, Miguel, Sofia Vera, and Giancarlo Visconti (2022). "Who does the caring? Gender disparities in COVID-19 attitudes and behaviors." Politics & Gender: 1-29.

Through an original phone survey in Peru, Carreras, Vera, and Visconti find that women are significantly more likely to support quarantine measures than men, and support lockdown measures in the future. They also find that women are significantly less likely to meet up with friends, eat out, or go to the mall compared to men. To account for gender differences, the authors use matching techniques to balance on covariates. They posit that the differences may be attributable to women’s care-giving and household duties. The paper has important implications on how policymakers communicate about lockdowns across gender lines.

Matt Lowe and Madeline McKelway (2022) “Coupling Labor Supply Decisions: An Experiment in India.” Working Paper.

While this paper is from November 2021, I couldn’t resist including it after reading Markus Goldstein’s summary this month (see here). It caught me by surprise and confirmed that we still understand little about intra-household bargaining between spouses, and it’s an area that requires a lot more research.

To re-summarize: Low and McKelway try to improve women’s labor force participation in India through an RCT with multiple intervention arms: they randomize whether a husband or a wife gets information on enrolling in a 4-month paid training on carpet making. But the after they give this information, they vary how the spouse who didn’t get the treatment hears about it: (1) the spouse who didn’t get the treatment is told that their partner was given information about the training; (2) the spouse who didn’t get the treatment is given three minutes to discuss the opportunity with their partner; (3) the spouse who didn’t get the treatment is given no information about their partner having received the treatment.

To my surprise (and to the surprise of many experts they polled in the paper), giving information to the spouse and their partner (#1 above) had no effect on enrollment (compared to #3 above)—regardless of whether the wife or husband received the original information. And even more surprisingly, discussion (#2 above) reduced enrollment by as much as 50% (compared to #3 above). The results are driven by couples who disagree on whether women should take up the job. Amongst couples who agree on the job, they see no enrollment uptake but amongst couples who disagree, they see a reduction in enrollment with both the information and discussion treatments.