I’ve been on hiatus, but here are some recent articles out on gender politics in LMICs that caught my attention.

Bush, S.S., Donno, D. and Zetterberg, P., 2024. International rewards for gender equality reforms in autocracies. American Political Science Review, 118(3), pp.1189-1203.

Bush, Donno, and Zetterberg theorize that for autocratic leaders, advancing women’s legal rights can showcase their low-cost democratic leanings without threatening their political survival. Such reputational gains may in turn increase international aid. In conjoint experiments conducted amongst staff of international development organizations in the U.S. and Europe, they find that countries that have more egalitarian economic rights for women (and to some extent, countries with gender quotas) are perceived more democratically. These reputational gains from gender rights seem to work similarly to reputational gains from allowing opposition countries to compete (a costlier and riskier move for authoritarian regimes). In the conjoint experiment, respondents are also more supportive of allowing foreign aid in countries with more economic rights for women. They replicate these findings in a survey of American citizens, and in interviews with elites. Even if governments don’t promote women’s rights in reality, these findings show how they can enhance their image with legal reforms—even if people are aware that these reforms may be a facade.

If you’re interested in gender politics in authoritarian regimes, check out December 2024’s special issue of Comparative Political Studies.

Guajardo, G. and Schwindt-Bayer, L.A., 2024. Women’s Representation and Corruption: Evidence from Local Audits in Mexico. Comparative Political Studies, 57(9), pp.1411-1440.

Using data from nearly 20 years of municipal audits of mayors in Mexico, Guajardo and Schwindt-Bayer study how revelations of corruption impact women’s election to office. They find that women are more likely to be elected as mayors when corruption audits occur, and they reveal spending irregularities. Voters and parties may think women are less corrupt, possibly leading to their election, but the authors also find that upon being elected, women and men do not behave differently. These findings echo similar work in the Indian setting, and show that perceptions of women as more honest political actors than men are sometimes sticky.

Haider, E.A. and Nooruddin, I., 2024. Well-Behaved Women: Engendering Political Interest in Public Opinion Research. Comparative Political Studies, 57(12), pp.2046-2079.

The article is premised on an interesting puzzle in Indian politics: “In India’s 2009 National Election Survey, 82% of female respondents reported voting, lagging just behind 85% of the male respondents who claimed they voted. Yet, in the same survey, only 32% of the women reported being interested in politics, compared to about 51% of the men. Such divergences are evident in other national surveys of the Indian electorate too.”

This problem troubles researchers throughout the developing world, where women are more likely to have difficulty responding to political knowledge or political discussion questions (see Lupu and Michelitch 2018). Haider and Nooruddin suggest that this anomaly may be attributable to the nature of data collection, wherein family members or neighbors are often present when enumerators conduct surveys. In the presence of others, women may often self-censor their interest in politics, which is considered taboo and non-normative. Across multiple surveys, they find that the presence of a bystander significantly increases the likelihood that women respond to political questions in a non-substantive way (e.g. by saying “don’t know” or “neither agree/disagree”). Women’s literacy seems to have a small attenuating effect. Comparatively, men tend to answer political questions similarly when they are alone or have bystanders. These findings highlight the importance of affording women privacy during surveys, though in reality, this is a difficult and sometimes an impossible task.

Heinzel, M., Weaver, C. and Jorgensen, S., 2024. Bureaucratic representation and gender mainstreaming in international organizations: evidence from the World Bank. American Political Science Review, pp.1-17.

What explains the disconnect between gender mainstreaming policies in international organizations (e.g. “action, financing, and programs at scale to support foundational wellbeing, economic participation and women's leadership” ) and their actual implementation? Using data from the World Bank staff, Heinzel, Weaver, and Jorgensen forward three main findings: (1) having policy on paper at least pushes a basic incorporation of gender mainstreaming; (2) having women staff on teams matters, as they are more likely to perceive gender mainstreaming as more relevant to achieving development goals of projects; (3) having women staff and women leaders on teams has a contagion effect; both women and men on these teams are more likely to take gender mainstreaming seriously. The authors do a good job of cautioning that these findings should not put the burden on women to forward gender-egalitarian policies, and that organizations should focus on “hiring more women and men staff members who possess specific gender expertise, promoting women into positions of authority, and increasing the overall number of gender advocates in the organization to change views engrained in bureaucratic subcultures”. Organizations should also be mindful of intersectional identities and expand the representation of women from LMICs, for instance.

Lindsey, S. and Koos, Carlo, 2024. Legacies of Wartime Sexual Violence: Survivors, Psychological Harms, and Mobilization. American Political Science Review, pp.1-17.

Linsey and Carlo take on a difficult question: Does sexual violence used during wartime impact social and political mobilization efforts of survivors or their families? They posit that when survivors and their families face threats of social stigma and isolation, they are more likely to reconnect with their communities through social and political investment. This is more likely in post-conflict or conflict settings where, in the absence of state-sponsored services, communities are essential sources of basic security. Through a primary survey of respondents in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which includes a list experiment, they find support for their theory. Exposure to sexual violence increases a number of socio-political outcomes amongst respondents, including their frequency of social interactions, engagement in local political or social organizations, public goods contributions, and participation in organizational leadership. These findings are important, especially given the dearth of knowledge on the topic. I also recommend reading the paper because it is carefully written, noting that these findings are not necessarily “good” news given the severity of the situations people face, while giving agency to survivors.

Jassal, N. and Barnhardt, S., 2024. Do women prefer in-group police officers? Survey and experimental evidence from India. Comparative political studies, 57(10), pp.1591-1633.

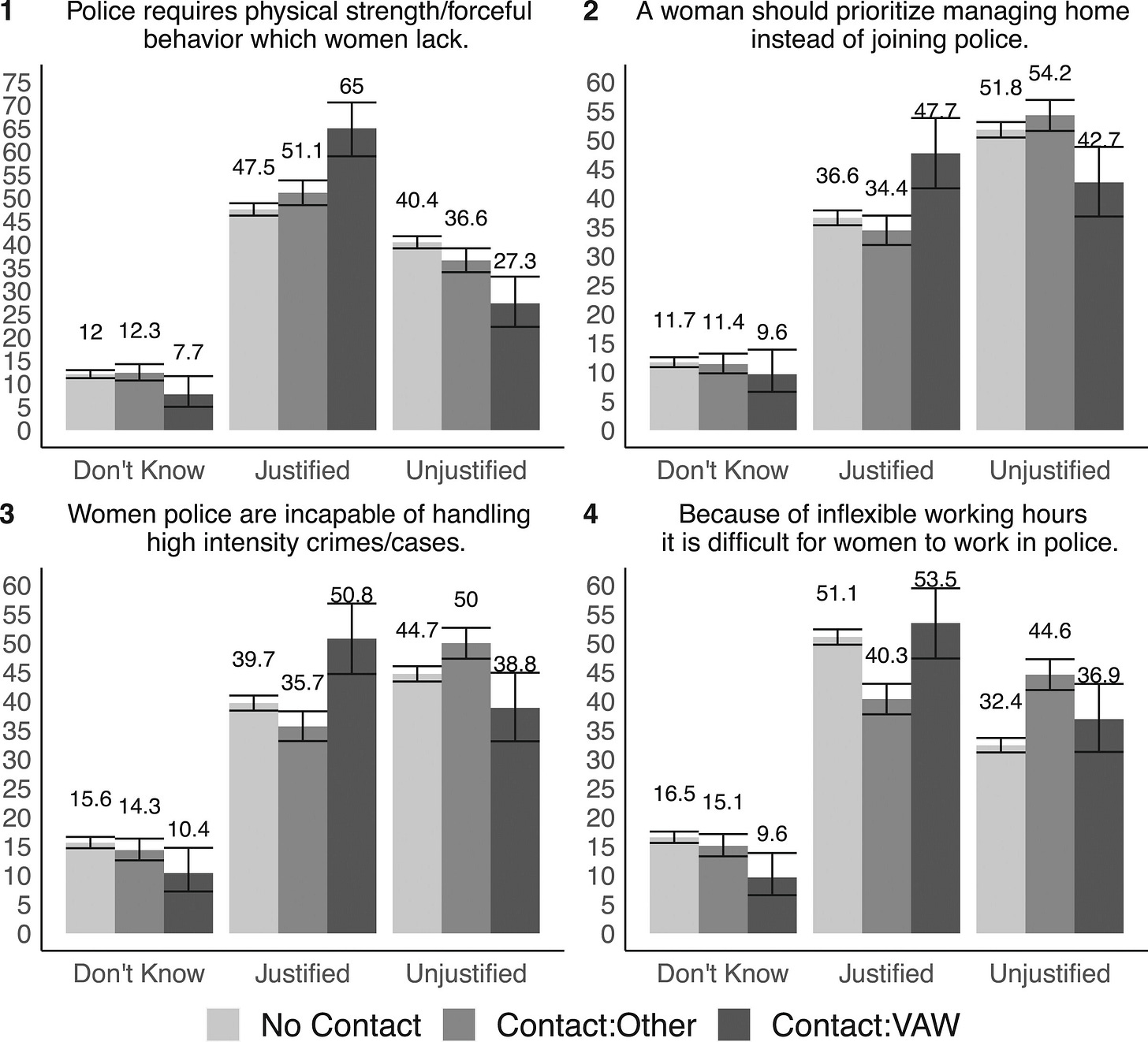

How do citizens perceive women police officers, and do women favor women police officers for cases of violence against women (VAW)? Jassal and Barnhardt study these questions in India using both descriptive and experimental data. The descriptive data from the 2019 CSDS survey (N≈15,000), summarized in the charts below, suggests that roughly half the respondents, regardless of gender (1st figure), do not think that women police officers are up to the mark. The 2nd figure suggests that these attitudes are also prevalent amongst respondents who report contact with the police, especially in cases of VAW. Importantly, however, self-reporting both contact and contract due to VAW may be prone to significant biases, and their supplementary figures show that respondents express fear approaching the police due to social stigma or harassment, either by officers or by their own families.

In a separate study, the authors answer the questions experimentally by showing respondents a video that mimics a news broadcast about a crime, while manipulating the gender of the police officer who investigated the crime and the crime itself (dowry harassment/rape (VAW), murder/kidnapping (non-VAW)). On average, respondents do not perceive women officers as more or less legitimate than male officers. However, policewomen are seen as less trustworthy and less likely to undertake procedural fairness for VAW cases, and this is particularly true for female respondents. The results suggest a need for more research on this topic because, as the authors note, the exact mechanisms are at times unclear, and the data points to diverging opinions for some outcomes and across the crimes (see supplementary appendix). Research is especially important as many countries, including India, typecast women in the police to investigate cases against women, and further policy prescriptions may be needed to ensure women are treated seriously—both by citizens and internally within organizations.

Shiran, M. 2024. Backlash after Quotas: Moral Panic as a Soft Repression Tactic against Women Politicians. Politics & Gender, 20(3), pp. 526–552.

Shiran examines elite reaction to the implementation of gender quotas in 10 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Using news articles from 2010-2021, they find that the introduction of gender quotas is associated with an uptick in conservative moral rhetoric in the media (measured using the Extended Moral Foundation Dictionary developed by psychologists). Though the data is limited to English language articles in countries and the data is descriptive in nature, the article points to one form of backlash against women’s political representation.