Did you present new Gender & Politics research at WPSA or MPSA and want us to mention your panel in our next newsletter? Have a new paper on gender and politics that you want us to feature in our next newsletter? Email us at annabelle.hutchinson@utah.edu.

Fernandes, J. M., Lopes da Fonseca, M., & Won, M. 2024. Political Competition and the Effectiveness of Gender Quotas: Evidence from Portugal. The Journal of Politics 86.1: 183-198.

When gender quotas are adopted, how should parties that previously opposed them react—should they signal that will accommodate to the new status quo, or maintain their opposition? Based on existing scholarship, the authors theorize that when parties do not face an electoral threat, they may be able to dismiss the expansion of gender representation and maintain their support base. However, when doing so risks reputational damage or electoral threats, parties may be better off “accommodating”—not necessarily supporting gender quotas but strategically emphasizing women’s issues. Doing so helps keep their core supporters while meeting the needs of the marketplace. They find support for this theory while examining 20 years of legislative debates (68,738 speeches with 4,052 observations for legislators!) in Portugal. They importantly find that parties accommodate by increasing the number of women who give speeches on the floor.

This is a superb study to expand a nuanced understanding of how political competition leads to engagement with women’s representation, which is increasingly relevant in settings like India which have, at least on paper, announced expansion of women’s quotas to national elections.

Kao, K., Lust, E., Shalaby, M. and Weiss, C.M., 2024. Female representation and legitimacy: Evidence from a harmonized experiment in Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia. American Political Science Review, 118(1), pp.495-503.

When will women’s incorporation in legislative bodies elicit backlash, and when will it elicit improved women’s representation? Studies from advanced democracies suggest that for the most part, women’s presence in decision-making groups improves evaluations of decisions that are made and trust in these groups. Kao et al. study the question in more patriarchal settings of Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia. Specifically, they conduct a phone-based survey experiment where they describe “an excerpt from a mock radio show describing a legislative committee that decided whether to raise penalties on domestic violence” (pg. 498). They fully randomize the committee’s gender composition and decision (expanding/limiting women’s rights).

The authors pre-registered their hypotheses that expected backlash from women’s inclusion in these committees, though they find the opposite. Respondents’ moderately agree with the committee’s decision when it is gender balanced, but the effects are much stronger (almost 8.5 times larger) when the decision expands women’s rights. They find similar results for an alternate outcome: respondents’ positively evaluate a committee when it is gender balanced and when they decide to expand women’s rights, though the effects are again stronger for the latter treatment. The authors run a similar analysis for a different issue area—littering, which is not gendered—and find similar results, wherein the decision improves legitimacy to a greater extend than the gender composition.

The study shows that gender balance matters even in settings where respondents openly condone sexism in their responses, and it may be due to a growing consensus on representation more globally. An important caveat, though, is that the precise composition of a group (e.g. how many women vs. men) may be much more important than balance alone; decisions, legitimacy, and the nature of deliberation may significant differ based on how groups are composed (the classic study on this is by Karpowitz and Mendelberg 2014, The Silent Sex). We’re excited to keep an eye out for some upcoming work on this in India by Brulé, Chauchard and Heinze, and across eight countries by Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo.

Tavits, Margit, Petra Schleiter, Jonathan Homola, And Dalston Ward. 2024. “Fathers’ Leave Reduces Sexist Attitudes.” American Political Science Review 118(1): 488–94.

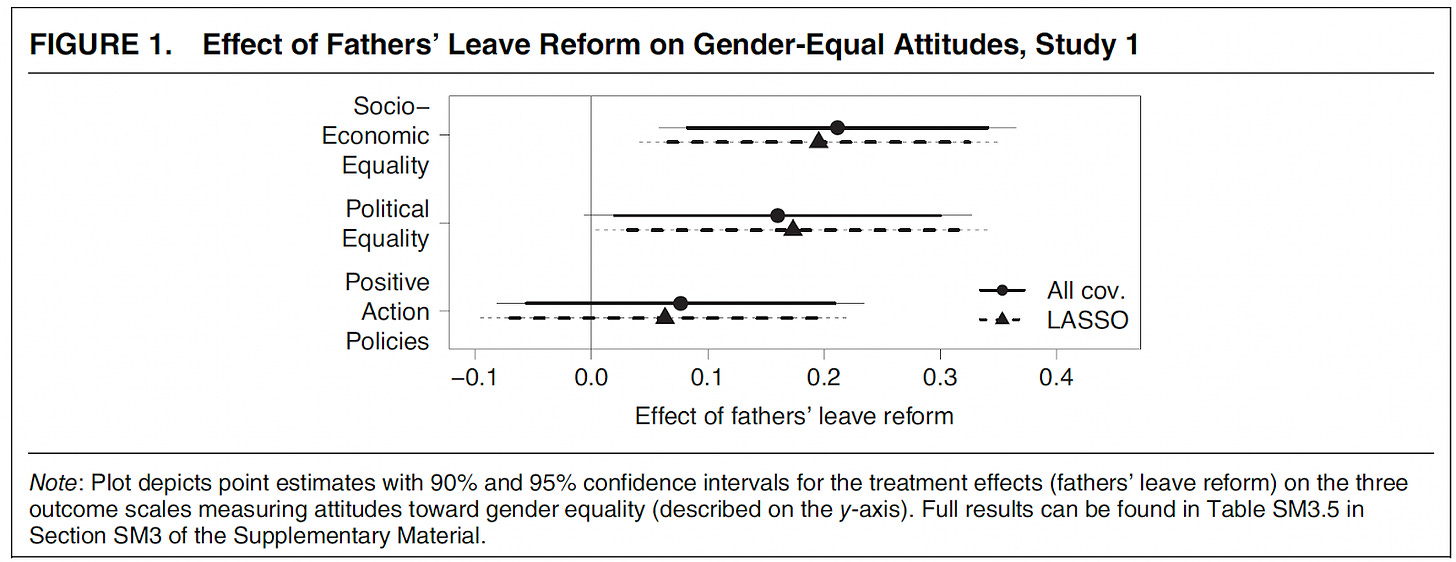

Does sexism decrease when fathers take paternity leave? This paper says “yes” in the context of Estonia, which tripled the amount of paternity leave available to fathers in 2020. The paper reaches its conclusions by utilizing a discontinuous feature of the timing of the policy rollout - parents whose babies were born before the cutoff were not eligible for the increased leave eligible for fathers and parents whose babies who were born after the cutoff were eligible for the extra leave for fathers.

The authors field two surveys - The first survey (which represents the control group who were not eligible for the increased leave) is of parents whose babies were born up to 6 months before the policy change and the second survey (which represents the treatment group who were eligible for the increased leave for fathers) is of parents whose babies were born up to 6 months after the policy change. (This identification strategy is convincing, especially because the authors show that parents don’t seem to plan pregnancies to strategically benefit from the policy.)

The data shows that parents who were eligible for the increased leave for fathers showed significant reductions in sexist attitudes related to socio-economic equality and political equality for women and men. Interestingly, men and women exhibit very similar patterns - in other words, both men and women decrease their sexist attitudes by similar magnitudes when it comes to socio-economic equality and political equality. (There are some heterogeneous differences with one measure, see paper if you’re curious about that.)

The authors also tested an informational treatment in a survey of the general public - does informing people about this increased leave for fathers change attitudes? Nope. (Although the psychological mechanism for why we might expect this informational treatment to cause a change in attitudes is unclear to me, Annabelle.) The data shows that an informational treatment did not change attitudes - direct exposure to the policy had to take place in order for attitude change to occur.

Slaughter, Christine, Chaya Crowder, and Christina Greer. 2024. “Black Women: Keepers of Democracy, the Democratic Process, and the Democratic Party.” Politics & Gender 20(1): 162–81.

This is a timely article, especially given the recent attention to a poll showing that Black voters may be less interested in voting for Biden than they have for other Democratic presidents. (To be clear, there is some debate on what we should take away from this poll, and I (Annabelle) am not totally convinced this is actually a trend.)

This article uses the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey to investigate the role that civic duty and partisanship play in Black women’s support for candidates and their political participation.

How does civic duty affect Black women’s political participation? This article shows that civic duty (measured by whether individuals think that voting is an effective means for having their voice heard) matters differently across race and gender when it comes to political participation. The authors “find that Black women are motivated by civic duty to participate in elections, whereas civic duty does not motivate Black men and white women.” In addition, civic duty matters more than political partisanship and candidate favorability in motivating Black women to vote. “Our article empirically demonstrates that Black women’s partisan identity is associated with their support for Democratic candidates; however, their faith in the democratic process, rather than their support for candidates, drives their turnout in presidential elections.”

Yan, A.N. and Berhnard, R. 2024. The Silenced Text: Field Experiments on Gendered Experiences of Political Participation. American Political Science Review, 118(1), 481–487.

Have you gotten a text from a political campaign before? This article shows that the exact same political text message is more likely to receive offensive, silencing, and withdrawal responses if the text is sent from a stereotypically female name (Jessica) compared to begin sent from a stereotypically male name (Michael) or gender ambiguous name (Taylor). However, at the same time, female-named texters were more likely to get responses and agreements to the requests in the text messages.

The authors partnered with a progressive political organization to conduct two field experiments in 2018, where they “randomized the apparent gender of volunteers during a texting (“Short Message Service,” or SMS) campaign meant to encourage a liberal organization’s supporters to attend rallies and call their representatives.”

Of note is that the field experiment in this study is LARGE. This study has enough statistical power to detect small effects. I worry that smaller studies with less observations would not be powered enough to detect the effects found in this study. So if you are interested in investigating whether these findings replicate in other settings, I’d pay attention to the power of your study.

We also recommend checking out these other great summaries of important work:

Anderson, Siwan. "The Complexity of Female Empowerment in India." Studies in Microeconomics (2024): 23210222241237030.

Heinze, Alyssa, Rachel Brulé, and Simon Chauchard. "Who Actually Governs? Gender Inequality and Political Representation in Rural India." (2024): (Summary by Simon Chauchard here.)

Prillaman, Soledad Artiz. The Patriarchal Political Order: The Making and Unraveling of the Gendered Participation Gap in India. Cambridge University Press, 2023. Summary in Alice Evans’ substack in the link below, though I think this summary doesn’t sufficiently acknowledge the point that in places like India, incremental improvements through self-help groups, such as the ones studied by Prillaman, are especially important in the absence of sweeping changes to gender norms and policies. Revolutionary changes are rarer and of course, more desirable, but activists work on these broader policies alongside grassroots levels efforts such as the one Prillaman studies. Our understanding of which micro-level interventions work to improve women’s agency is just as important as which macro-level ones do.

Thanks for reading Gender & Politics Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.